‘A shock to the system’: looking back on the 1984 New York subway shooting

The new season of Leon Neyfakh’s Fiasco podcast relives a bleak chapter of US history when a white man became a folk hero after shooting four black youths

When Leon Neyfakh moved to New York in 2007, he felt perfectly safe. “A lot of people my age have this experience of their parents or other folks who remember the old New York being like, ‘Are you sure that you want to live there? Is it safe to go out at night?’” the 38-year-old, blue-shirted and bespectacled, says via Zoom from Brooklyn. “What are you talking about? You can be on the subway at 3am in New York City now and you’re not afraid.”

But, Neyfakh acknowledges, that picture has become more complicated since the coronavirus pandemic with a perception of danger returning to the city in general and the subway in particular. In May, when military veteran Daniel Penny put fellow train rider Jordan Neely in a fatal chokehold, he claimed that he had acted in defence of himself and other passengers.

Penny pleaded not guilty to charges of manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide. Protesters decried Penny, who is white, as a vigilante and described the death of Neely, who is Black, as a lynching. But he was hailed as a hero by Republican politicians and supporters, who raised millions for his defence. Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal called him “the subway samaritan”.

By the time this horror unfolded, journalist Neyfakh was already deep into making the sixth season of his Audible podcast, Fiasco, about a subject with inescapable parallels. Vigilante explores a crime that defined an era: the shooting of four Black teenagers by a white man named Bernard Goetz on the subway in 1984.

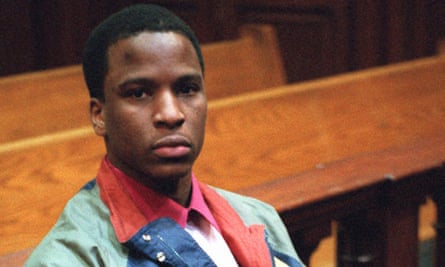

The podcast asks why Goetz received an outpouring of public support, and ultimately escaped conviction for attempted murder, while the four victims – Darrell Cabey, Troy Canty, Barry Allen and James Ramseur – were marginalised and misunderstood. And through interviews with family members and neighbours, it goes a long way to correcting that imbalance.

Neyfakh, host of Fiasco and co-creator of Slow Burn, which grippingly excavated Watergate and the Bill Clinton impeachment, says: “We find over and over again, even with the most monumental stories like Watergate, for example, the process” – he waggles his fingers in the air for emphasis – “of collective memory is very unpredictable and the things that get stuck in the public imagination are not always correct and they’re not always the most interesting parts.

“This felt like a story that we could break some new ground on and one in which we could address a lot of issues that are of great relevance today and do so through this prism. I always think of our shows as being raw material for people to think through the world around them in the present day that just has different inputs.

“In the same way, when people listened to the Watergate season of Slow Burn, the story of Nixon let them think through what was happening with Trump but it didn’t require talking about Trump literally.”

The first episode of Vigilante paints a picture of New York in the 1980s – graffiti-coated subway carriages, sex workers in Times Square, rampant drugs and violent crime, the sort of world that Alec Guinness’s Obi-Wan Kenobi might have described as a wretched hive of scum and villainy. The rate of major felonies – murder, rape, robbery, assault – was about five times higher than now.

Neyfakh elaborates: “People say that New York today is unrecognisable to someone who came of age in the 70s or 80s version of it, and a big part of that is crime and the sense that people walked around with that ‘behind every corner might be a guy in a trench coat who’s going to hold them up’.

“Times Square was a very different place than it is today. Today, there’s Muppets and Looney Tunes walking around. Back then, it was kind of known as a den of sin where you didn’t want to go after dark. New York in the 80s was nationally thought of as a dangerous place and it was: the numbers were quite staggering and they were much higher than than they are today.

“That was a trend that was true around the United States in big cities. The number of reported major crimes in the US had tripled since the mid 1960s and so there is the sense that the country was going to hell and that New York was going to hell; it had already gotten there. People talked about it as a cesspool. The presence of graffiti all over and in every subway car made people feel like no one was in charge.”

On 22 December 1984, Goetz, a 37-year-old electronics engineer, was riding the subway when four Black teenagers asked him for money; he later told police he feared they were going to rob him. He pulled out a handgun (bought in Florida and brought to New York illegally) and opened fire, shooting all four of the young men. Three recovered but Cabey was paralysed and suffered permanent brain damage.

Goetz initially fled the scene but later turned himself in to the authorities. He faced charges related to the shooting and went to trial in 1987. He was acquitted of attempted murder, after a jury concluded that his fear of being a crime victim was reasonable, but found guilty of illegal firearms possession. In 1996 a civil jury found the shooting unjustified and awarded Cabey damages.

The shooting held up a mirror to American society, sparking debates about vigilantism, self-defence, gun control and race relations. Some people saw Goetz as a folk hero, standing up to crime in a menacing city, while others condemned him for taking the law into his own hands with excessive force. His victims were marginalised and attacked in the press.

Neyfakh reflects: “The Goetz shooting became a sensation and cause for so many people because people were inclined to see him as someone who stood up to the crime problem. The outpouring of support for him was immense and very public. After Goetz shot these four teenagers he disappeared into the subway tunnel and went on the run for about nine days.

“During that period, no one knew who he was. He took on the status of a folk hero, in part because people didn’t know anything about him. The NYPD set up a tip line for anyone who knew anything about who this guy might be as they were looking for him. Instead of getting tips, they were flooded with phone messages from people who said this guy should run for mayor, whoever he is.”

after newsletter promotion

The media played a big part in shaping the narrative and is the subject of episode two. “This shooting happened towards the beginning of Rupert Murdoch’s career in America as a newspaperman. The New York Post [owned by Murdoch] and the Daily News were locked in this very intense tabloid war. Not to overstate things but the Goetz story was fodder for that media war. It’s an important early chapter in the evolution of the Rupert Murdoch empire in the United States,” Neyfakh says.

But what shocked Neyfakh most was the volume of vitriol and hatred aimed directly at the victims. “They were described in the press as street toughs. People didn’t have a lot of time for making distinctions between them or understanding who they were or what kind of lives they had led. There was not a lot of interest,” he says.

“Darrell Cabey’s sister, who was much younger than him, told us about growing up not really knowing that much about what happened to her brother but occasionally getting a crazy phone from some lunatic who wanted to say something nasty to them.”

Two lawyers who represented Cabey and his mother in a civil lawsuit against Goetz shared hate mail that the Cabey family had received. “It’s a shock to the system to imagine someone so angry at this person who got shot and so motivated to tell them they wish they’d been killed or to tell his mother that she should have had an abortion,” Neyfakh says.

“There are always going to be people who have those impulses and indulge those impulses. It’s probably not something that even a lot of social progress or political progress can just eradicate.”

The National Rifle Association seized on the case as an opportunity to promote gun ownership and expand their market beyond rural areas to cities. As for Goetz, he is still living, devoted to squirrels and vegetarianism and entirely unrepentant.

Neyfakh notes: “He never showed remorse. He said in an interview that he gave, which is on tape and features quite prominently in the show, that he wished he had done worse. He said, ‘I would gouge their eyes out if I could have and I wish I had killed them.’ Goetz felt he had done what he had to do basically and he’s held that line ever since.”

The journalist resists the temptation to condemn the past as a foreign country or assert moral superiority for the present. While much has happened in the past four decades – the election of Barack Obama, a racial reckoning over the police killing of George Floyd – it would be naive to assume that such a case would play entirely differently today. Kyle Rittenhouse, who at 17 killed two people at an anti-racism protest in 2020, was acquitted on all charges and embraced as a mascot by Republicans.

Neyfakh recalls: “I experienced this a little bit when we made season two of Slow Burn about the Clinton impeachment and Monica Lewinsky and people were like, ‘Boy, we’ve come a long way, we’d never treat a woman this way now.’ Everyone got to feel good about how much progress we’ve made with the culture. There is a little bit of a risk sometimes when we look back at the past and feel flattered. We shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that you can never really tell how much things have changed.”

-

Fiasco: Vigilante is now available on Audible