Charlotta Bass of the California Eagle, with Paul Robeson, ca. 1949 / Los Angeles Daily News (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license)

Today with the wars on Gaza, in Ukraine, and the war that seems to be planned against China, there is a huge gap between what is being said on alternative sites on the internet and what is being said in the mainstream media (MSM).

Recently, for example, on the second anniversary of the war in Ukraine, the New York Times ran a (Pentagon and State Department) account of the war (started by Russia on Feb. 24, 2022), its reasons for being (Putin’s aggressiveness which now threatens all Europe), and its possible outcome (there is none, just continual fighting).

That analysis contrasted sharply on every point with Global South scholar Vijay Prashad’s view featured on a podcast, on YouTube, and a streaming series.

Prashad noted that what he called “the Ukrainian Civil War” started nearly a decade earlier in 2014 after a U.S.-backed coup aided by Ukrainian Nazis overthrew the elected head of the country and started bombing the Russian-majority Donetsk region, killing 14,000 people. Russia’s “Special Military Operation” then was the response to NATO threatening to absorb Ukraine and put missiles on Russia’s border, with the Russians, almost since the beginning of the SMO, suing for peace in an agreement that was sabotaged by Boris Johnson and the West.

The line of demarcation between corporate media—and the political class being led by the nose by the weapon and fossil fuel industries and by powerful lobbying groups such as Israel’s AIPAC—and the now legion of podcasters, YouTubers, bloggers, and online publications that are every day standing against this deadly barrage is more sharply drawn than ever.

It’s independent social media versus what seems more and more like anti-social, bellicose, and belligerent corporate media.

Looking back to an earlier era

Perhaps not surprisingly, these lines can also be traced beyond today’s internet alternative media explosion to an earlier period where, with the outlawing and excising of many of the ideas and social practices of the more collectivist and worker-oriented New Deal, there was an equally momentous battle between the corporate media, in this case, the dominant newspapers, and other newspapers which spoke to and represented audiences left out of the corporate consensus.

Nowhere was this difference starker than in Los Angeles, between the paper of record, or at least that with the leading circulation, the Los Angeles Times, which had also launched a second paper and its own television station, and the African-American paper The California Eagle, which began in the 1920s and championed the rights of Black people to own property where they wanted in a heavily segregated city.

The former was run by the Chandler family, historically rabidly anti-union champions of an Anglo Los Angeles spread out across the county in suburban, individual, single-family homes with a system of freeways and building projects that benefitted Chandler real estate interests.

The Times utilized and promoted “anti-communism” as a way of smearing its opponents. The Eagle’s editor, Charlotta Bass, stood instead for the vision of an integrated and equal Los Angeles, defending public transit and community institutions, and welcoming peaceful and harmonious intercourse with the socialist world of the USSR and China.

These differences are sharply illustrated in my latest Harry Palmer Detective Novel, The House That Buff Built, where Harry, in the course of helping his Chinese client to integrate the town of Torrance, encounters both Charlotta and the Chandlers and is stunned by the difference between The Eagle, Bass’s modest paper, and the gigantic octopus that was the L.A. Times.

These differences are sharply illustrated in my latest Harry Palmer Detective Novel, The House That Buff Built, where Harry, in the course of helping his Chinese client to integrate the town of Torrance, encounters both Charlotta and the Chandlers and is stunned by the difference between The Eagle, Bass’s modest paper, and the gigantic octopus that was the L.A. Times.

While The Eagle was supported by its African-American community, the Times was the largest newspaper in terms of circulation in the country’s most booming region in the postwar era, read and advertised in by the city’s elite. In 1950, the Times, though gradually improving professionally, was still, according to David Halberstam in The Powers That Be, opposed to original unbiased reporting and filled with wire service briefs, dispatches from city corporations that it partially controlled, and “slanted political coverage that read more like memos from—and to—the Republican Central Committee than journalism.”

Housing in L.A.: To segregate or not to segregate

A primary area of disagreement between the two newspapers was segregation versus inclusion in a battle over Los Angeles housing.

The Chandlers’ vision was of an Anglo Los Angeles with white flight peopling the suburbs and its new inhabitants maneuvering through a system of freeways with the land, the building materials for the roadways, and even the rubber for the automobiles coming from Chandler companies.

The city meanwhile would be remade, with the Times favoring a gutting of the low-income habitats of Bunker Hill and Mexican-American villages in what is now Chavez Ravine and the buildup of the Northern part of downtown near the Times building.

Norman Chandler, the heir to the Times fortune in the 1950s, was told when he took over the paper that the key to the editorial page was to “think of what is good for real estate.” The paper actively promoted these interests and this demolition. “Our future,” Dorothy Chandler tells Harry in a candid admission, “was not in trying to be a paper for the Black or the Latino populations or the low-income white population.”

The Eagle meanwhile was instrumental in furthering Black expansion out of the tight quarters around Central Avenue where African-Americans had been confined and moving into homes both North and South of this area. Prior to this period, a method of enforcement of segregation was restrictive covenants which forbade homeowners from selling to the “Negro or Mongolian” races, thus also limiting the Chinese to Chinatown. In 1948, the Supreme Court outlawed this use in a case argued by Eagle reporter Loren Miller, who would succeed Bass in running the paper in 1951.

A major site where segregation was either fostered or contested was the society or women’s pages of each paper. Norman’s wife Dorothy Chandler, nicknamed Buffy or Buff, took over those pages in the Times and used them to blackmail wealthy donors to support her vision of “modern” Los Angeles built around what would become gleaming corporate skyscrapers and cultural centers perched on a demolished Bunker Hill.

Meanwhile, Charlotta Bass used the back pages of The Eagle to create women’s groups which she called on for support when homeowners moving out of Central Avenue were besieged by aggressive “neighbors” who attempted to drive them out of their homes—and this was after the Supreme Court decision, which applied only to federal housing projects.

As Harry puts it in the novel, “I thought about the contrast between The California Eagle’s Bass, who used the society pages of her publication to rally Negro ladies to defend the hard-won housing gains of her readers trying to secure a better place in Dorothy’s society, and Dorothy’s organizing of the rich [through the Times society pages] in a way that excluded everyone else and furthered their own power.”

Collectivist vs. individualist futures

Two different visions of the city were professed by each publication. The Times was rabidly anti-union, going back to its founder, General Otis, who called union leaders “corpse defacers” and unions “the poison of the American future,” and actively resisted unionization at the paper. The Times instead favored dividing working people by breaking up urban neighborhoods and housing families in more isolated, individual units in the suburbs.

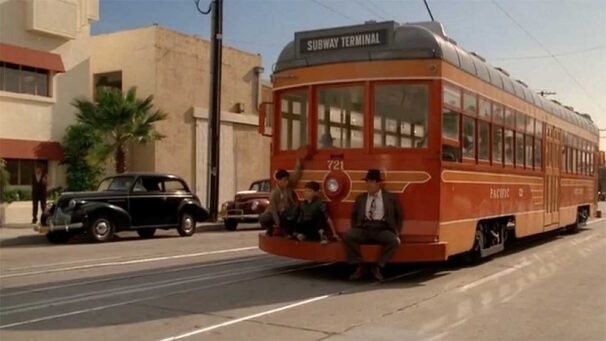

The newspaper was against public transportation, instead promoting the individual in his or her own car and declaring on its editorial pages that “Southern California throbs in unison with the purring motors of its automobiles.” The paper championed the building of the country’s first freeway, which connected the ultra-rich old-wealth community of Pasadena with downtown Los Angeles and was then followed by the Harbor, Hollywood, Long Beach, and Santa Ana freeways.

The Eagle, on the other hand, defended the cheap and environmentally effective mass transit trolleys and buses which ferried its readers to and from work and was also a champion of unions, many of which were integrated and had African-American women not only as members but also as leaders in the factories that had sprung up as Southern California became the country’s main motor of production during the Second World War.

When Harry visits Bass at the office of The Eagle, she lays out this difference. “She described a city that on one side was made up of the Klan, the National Rifle Association, and property restriction organizations, and on the other the labor movement, the Negro, Jewish, Mexican, and Chinese minorities; ‘those people who do the work in the city and who are fighting against the threat of a new fascism at home.’”

Cold War vs. enduring peace

Founder General Otis had led a slaughter against Filipino women and children in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, named his homes “The Bivouac” and “The Outpost,” and organized the Times staff in an anti-union “phalanx” armed with rifles and shotguns.

Following his lead, the Times in the 1950s under Norman Chandler was a huge supporter of the Cold War and the anti-communist campaign. The Times pushed Richard Nixon in his successful run for the Senate in 1950, calling his red-baiting attack on Alger Hiss “heroic,” as well as being a firm backer of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s paranoid finding of communists next door to every American, lauding McCarthy’s bullying tactics as speaking softly and “carrying the big stick of logic.”

The Times used the generalized attack on what amounted to the reforms of Roosevelt’s New Deal to eventually install their own candidate for mayor, Norman Poulson, in 1952, who would veto what the paper saw as the eyesore of public housing and apply the Cold War policy of “containment” on the homefront to keep minority communities bottled up and limit expansion, and expel them as needed—to build Dodger Stadium and the downtown Music Center, for example.

On the other hand, The Eagle in its pages constantly favored peace and understanding with both the Soviet Union and the then-emerging socialist state of China. The paper covered a global conference on women’s rights in Beijing in 1949 which promoted a transnational anti-colonial platform for women fighting imperial oppression, covered a speech by Paul Robeson’s wife Eslanda in China, and reported positively on the gains of the revolution as distributing land “so now everyone has a home, a chance to go to school, and a job with women treated as equals.”

The paper also had a diametrically opposed view of containment, terming the reinstitution of personal homeowner restrictions in the wake of the Supreme Court decision “re-covenanting,” supporting activists who “made it clear that they had not fought to destroy fascism abroad only to have it camping on their doorsteps at home.”

As for the real postwar menace and threat, in the novel Charlotta Bass, who has just been assaulted by a gang of white teens, tells Harry that “They always talk about Negro and Mexican violence, but in reality, and it’s true in your case with the Chinese as well, the real fear is white violence.”

The past as mirror of the future

Today, with the mainstream media more adamantly than ever pushing for war at every opportunity and operating to confuse their audience and make what is crystal clear unclear—the recent example of Israel’s massacring starving Palestinians as they clamored for food presented in the Western press as not a mass killing of a defenseless people but as a chaotic riot by a stampeding mob—the 1950s example of both the strident self-aggrandizing and bellicose Los Angeles Times and the parallel example of the courageous, resistant California Eagle tirelessly campaigning for equality and peace is more trenchant than ever.

With The New York Times recently the recipient of the prestigious Polk Award for its coverage of the assault on Gaza, a coverage that for the most part was distinguished by its shallowness, lacking any backgrounding or treatment of the conflict pre-October 7, 2023, Harry’s verdict on the Chandlers’ imposing their will in the creation of modern Los Angeles also stands as a warning of a too-powerful media operating in a vacuum.

“The paper was everywhere. Buff ’s ‘civilizing mission’ was part of remaking a town that, when it resisted that mission, might be compelled by whatever means necessary to accept it.”