Jeremy Hayes was getting ready to take his three sons to the pool when he heard a loud rap on the door.

Hours earlier, his wife Jennifer had gotten to Nashville after finishing a work trip. The Hayeses live in Illinois but bought an apartment on Church Street in 2021 as a weekend getaway — a refuge where the family felt safe. They like to walk to Sounds games and concerts. On that Friday in late July, Jackson (age 10), Brady (8) and Austin (5) were scrambling around the apartment collecting bathing suits and towels.

“We really like it in Nashville,” Hayes tells the Scene weeks later. “We probably spend 25 percent of our time down there. We bring friends and family, do the Broadway thing. With the exception of this incident, we really enjoy Nashville.”

The knocking got aggressive.

“Like a SWAT team,” Hayes remembers. “So I opened the door, and there was a person pointing a gun directly at my chest.”

Jennifer stood next to him. Brady and Austin stood behind their parents. Police later decided that Brady was in the line of fire — Austin’s statement to the police could mean a fourth felony charge for the Hayeses’ across-the-hall neighbor, Chris Weathers, who was booked three days later on three charges of aggravated assault. Hayes had never met the man. That afternoon, Weathers stood in the hallway shirtless, allegedly aiming a black handgun.

“He told us to shut our kids up, or he would,” remembers Hayes.

Jeremy expected the gun to go off. After some yelling and a few tense seconds, he shut the door. The family huddled in the bedroom while Jennifer notified the front desk and called the police. By the time the cops arrived to take statements, Austin had cried himself to sleep. The family headed back to the Chicago suburbs that night. Jennifer has since been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Both parents have done extensive therapy with the boys, who don’t participate in school lockdown drills.

“We’ve never really seen the need for guns in our household, but the first thing we did when we got back was register with the state,” says Hayes. Unlike Tennessee, Illinois requires a 72-hour waiting period and a permit to own a gun. “When that comes in, we plan on buying a gun for Illinois and a gun for Nashville. We’ll lock them up and take proper training and all that. We always considered Nashville very safe, but that incident changed us. We want to be prepared if something else were to occur. We don’t want to be out there with no protection.”

Typical gun violence charts, graphs and tables don’t capture victims like the Hayes family, which, three months later, lives with the psychological and emotional fallout of a gun that never went off. Or elementary school children, versed in active-shooter drills, who teach their parents about “hard corners,” the hidden spots of a room not visible from an outside window or door.

In the past decade, gun violence has pervaded the everyday. Mass shootings have shattered expectations of safety at elementary schools, high schools, concerts, mosques, churches, malls, movie theaters, grocery stores, bars — sacred spaces that previously functioned as havens of public life. Regular and random gun use — like the September road rage incident on I-440 that put bullet holes in Chancery Court Judge I’Ashea Myles’ Prius, or the shooting of a German shepherd at Percy Warner Park two weeks later — defy expectations of safety anywhere.

Unable to rely on lawmakers to regulate guns, some Tennesseans have decided to risk gun ownership to help manage the fear and anxiety of living in a nation full of weapons. While mass shootings erode Americans’ shared sense of security, it’s retaliatory gun violence, intimate partner violence, gun accidents and suicide by firearm that kill us in higher numbers — all risks that dramatically increase by inviting a weapon into one’s home. These owners hope to mitigate the statistics with extensive safety measures, regular training and the weighty sense of responsibility that accompanies keeping a firearm, consciously distancing themselves from both the gun-obsessed maximalists and negligent owners. Those who spoke to the Scene for this story justified their decision with different versions of the same sentiment: I am anti-gun for everyone except myself.

America’s civilian gun ownership far exceeds every other country in the world. There are more guns in this country than people, mostly concentrated in the hands of “super-owners,” a term used by Vanderbilt professor Jonathan Metzl in his landmark 2019 book Dying of Whiteness. This majority-white, majority-male group captures the furthest extreme of gun ownership and often follows a cultural obsession with Second Amendment rights and escalatory practices like open carrying.

For decades, the National Rifle Association and other extreme pro-gun interests have been the sole forces defining American gun ownership, Metzl argues in his new book — a project that springs from the public response after the 2018 Waffle House shooting in Antioch.

“Even though he was doing everything possible to flash warning signs, Travis Reinking coded as a patriot to police, to communities, to his parents, up until the moment he pulled the trigger,” Metzl says of the Waffle House shooter, who was ultimately convicted on four counts of first-degree murder. “Then after he pulled the trigger, the state apparatus of Tennessee mobilized to protect the rights of people like him. This issue of white male gun ownership is not fully addressed if the gun safety side is only looking at shootings.”

Metzl points to bigger, structural reasons for today’s arms race: large swaths of the country gripped by fear. Aspects of life seemingly unrelated to guns — like increased green space and more street lights — correlate with lower gun violence, he says. Every Tuesday afternoon, Metzl packs a Vanderbilt lecture hall with undergrads for his fall course, Guns in America.

“You could take someone who’s a conservative gun owner in America and put them on a train in Tokyo, and they would probably feel like, ‘I don’t need my gun right now,’ because you don’t fear somebody else has a gun,” Metzl says. “There are societal checks in place. The triggers people associate with why they need a gun are about the breakdown of community infrastructure, the lack of investment in civic space, lack of trust in communal structures. We need to take people’s concerns about fear and safety seriously and really try to address them.”

In August, state lawmakers came back to Nashville for a special legislative session called by Gov. Bill Lee. Lee announced the session amid public backlash against the state’s lax gun laws. In a press release issued on May 8, the governor said the session was intended to “keep Tennessee communities safe and preserve the constitutional rights of law-abiding citizens.”

In March, an individual armed with tactical gear, two rifles and a handgun killed three 9-year-old children and three adults at the Covenant School in Green Hills before being shot to death by Nashville police. The killings roiled the city and prompted immediate, sustained protest at the state Capitol, where pro-gun lawmakers hold supermajorities in the House and Senate.

Lee’s response implied a potential revision of Tennessee’s legal protections for firearms — a conservative credo that has become essentially unlimited in Tennessee over the past decade. August came and went. State leaders passed one piece of legislation related to guns, a mishmash of statutes exempting firearm safety products from sales taxes, enabling Tennesseans to request free state gun locks and mandating safe-storage content in handgun training courses. After reframing the session as a crime-focused work session, Lee delivered closing remarks. He praised Covenant parents for being a part of the public “engagement process.”

“My daughter lost 50 percent of her hearing in her left ear — I can’t stand the thought of having another child be shot at in school,” says Melissa Alexander, the mom of a Covenant student who survived the March shooting. “Or for a parent to go through the chaos of trying to figure out if their child is alive. Or to lose their babies, and not be able to tuck them in at night. All because we’re so concerned with some right to bear arms that’s talking about a stupid militia. We are not in a war. Let’s stop pretending and creating a war amongst each other.”

Alexander, a Republican, has publicly blasted her own party for its weak stances on gun control. The Scene reached out to several Republican lawmakers for comment on this story and requested interviews with members of the House and Senate via the GOP’s communications staff. Ultimately our request for comment was not fulfilled.

Tennessee’s experiment against gun control began with the 2007 passage of a so-called Stand Your Ground law, which enhanced legal protections for civilians to use deadly force. The next year, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed citizen gun rights with a 5-4 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller, energizing national opposition to gun control. Four months later, Barack Obama was elected president, followed shortly by a historic spike in gun and ammunition sales. (A much larger spike occurred in 2012, in the months following Obama’s reelection and the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary; similar spikes continue to follow events of mass gun violence.)

The Tennessee legislature gradually struck down more gun regulations throughout the 2010s. First, lawmakers expanded the rights of permit holders, allowing them to store loaded guns in car trunks and to carry them at bars, public parks, playgrounds, school campuses and on buses. In 2019, the House and Senate gutted requirements for a gun permit before getting rid of required permitting altogether in 2021. “Permitless carry,” championed by ranking Republicans William Lamberth in the House and Jack Johnson in the Senate, signed away the state’s last line of firearm oversight.

Spurred by the tragedy at Covenant, Tennesseans across the political spectrum have become fixated on gun control as a litmus test for future voting.

“It is important for voices like mine to speak out,” says Jordan Huffman, Nashville’s newly elected councilmember for parts of Donelson, Hermitage and Old Hickory. “It is critical for people like me who grew up around guns, who look like me — a bald guy with a beard — to talk about responsible gun ownership.”

We speak in his condo while Huffman’s 2-year-old son Will toddles across the kitchen and living room.

Metro Councilmember Jordan Huffman

Originally from Greeneville in East Tennessee, Huffman grew up in a family of gun owners. Huffman says becoming a dad made him take the security of his home and family more seriously. He and his wife have gun safety training and know how to use a handgun, which they keep locked in a fingerprinted safe on a shelf in their closet. He disabled the combination lock on the off chance that Will finds the safe and guesses right. They occasionally hear hostile gunfire in their neighborhood, says Huffman, and a firearm is a last resort.

“We have an issue with fear in this country,” he says. “Fear that something will happen. I saw this fear when I was campaigning and in East Tennessee. It happens when you listen to propaganda all day — commonsense voices of reason get drowned out. There is a big difference between owning an assault rifle and owning a handgun that’s locked away and stored safely. I like guns. I grew up around guns. I like shooting guns. But you can’t say there’s not a problem in this country right now.”

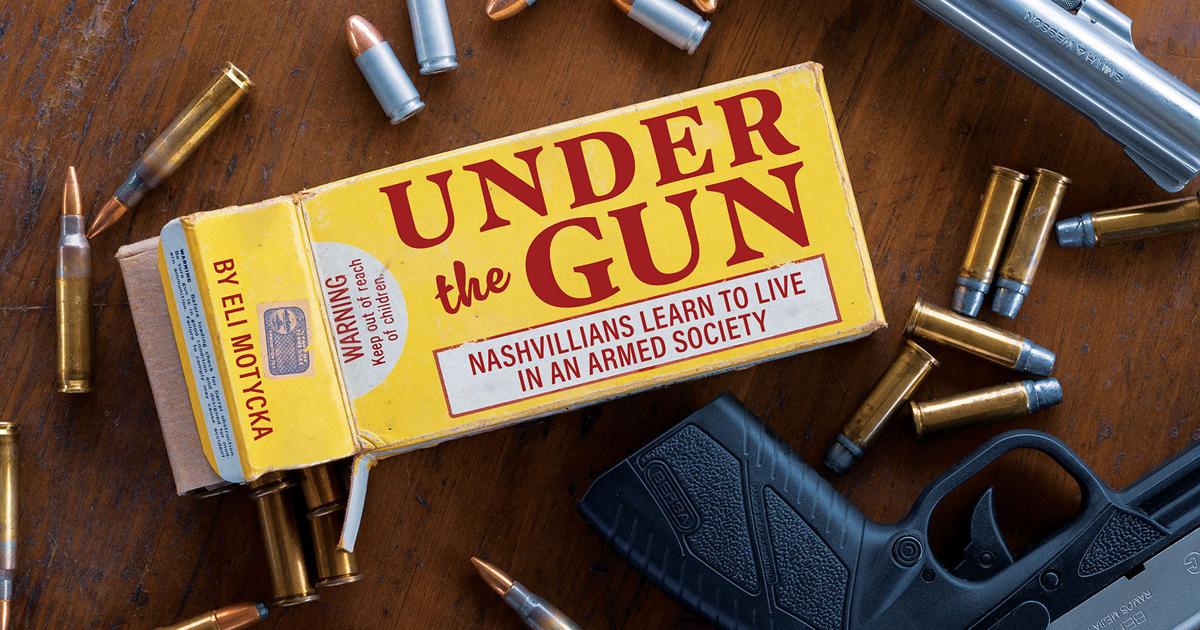

In Tennessee, a single piece of mandatory reporting remains: federal form 4473, a record of official firearm sales. Guns that change hands in private sales, transfers, loans, gifts or thefts leave no records. Beth Joslin Roth, a longtime advocate for gun safety and a staffer for state Sen. Heidi Campbell, collects statewide gun statistics, legislative history, legal loopholes and shooting data at the website Tennessee Under the Gun. As of this writing, Nashville police were aware of 1,278 guns stolen in Davidson County this year. Nearly 8,000 guns have been reported stolen in Nashville since Jan. 1, 2019. Gun theft, particularly from unlocked cars, is so bad that police issue regular press releases reminding gun owners to lock their vehicles. In early September, a police rifle, riot gear and a police shotgun were stolen from marked MNPD vehicles in two separate incidents.

“Officers throughout the police department are being reminded to properly secure their firearms,” police told WSMV at the time.

A purely voluntary permitting process, thefts and a robust private market render statistics on Tennessee gun ownership unreliable. Tennessee annually reported more than 100,000 legal gun owners before state law gutted the permitting process. The state makes a lot of guns — 185,000 in 2021 according to the ATF, mostly manufactured in Gallatin by Beretta, the Italian gun giant that moved its U.S. headquarters to Tennessee in 2016. Smith & Wesson moved its headquarters to East Tennessee this year after more than 100 years in Massachusetts. Both companies cited Tennessee’s gun-friendly political climate in explaining their moves.

The thing about having more guns: Sometimes they go off.

Mass shootings like the ones at the Covenant School and Waffle House rock a city, dominating headlines and casual conversation for weeks. These events politicize bystanders and shape community narratives, but they account for just a fraction of the city’s gun violence.

Last year, Dr. Jay Wellons, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital, published All That Moves Us, a book about what he sees on the operating table. Vanderbilt is the region’s only Level 1 trauma center, the state’s highest designation for its most urgent medical emergencies. Wellons is a self-proclaimed “son of the South,” and his experience with firearms includes both growing up with hunting rifles and operating on gunshot wounds, a central theme in All That Moves Us.

“As doctors, we can only do what we are trained to do if a patient makes it to the hospital alive,” Wellons tells the Scene.

He remembers the surge of trauma physicians moving toward the door after the shooting at Covenant.

“They finally told us nobody would be coming to the ER that was alive,” says Wellons. “The sadness and grief was palpable. We were ready to save lives. That’s what we are trained to do. That’s what we want to do.”

The survivability of a child with a gunshot wound is less than 5 percent, says Wellons, because of how the bullet tears through tissue. At high velocities, a single round creates an air pocket that rips a path through the body in a process called cavitation. When it hits bone, the bullet fragments. When it fragments, it begins to tumble, wreaking havoc across arteries and organs. Wellons draws a graph: Two colorful lines signify childhood cancer and car deaths decreasing over time. A third, fatal gunshot injuries, increases gradually. Then sharply.

“Throughout history, medicine has learned lessons from weapons of war and taken them back to nonmilitary society,” says Wellons. “I do not see the lesson here. The lesson is that we have too many guns in society. We’ve lost. We are winning the war against car accidents. We are winning against childhood cancer. I want people to understand that having a society with guns is going to cost us some proportion of our children.”

So far this year, Nashville police have logged 3,497 incidents of violent threats involving firearms, like the threat that shook the Hayes family. There have been exactly 300 nonfatal shootings and 77 fatal shootings in 2023, on pace to match 2022. About 75 percent of victims are Black. Most are men, though women in domestic violence situations face a particular epidemic of gun violence in Nashville, amplified by failed state oversight, according to reporting this summer from WPLN’s Paige Pfleger.

Of these incidents, most are scattered across North Nashville, Antioch and Madison. Zoom in and see three distinct clusters near Edgehill, Napier-Sudekum and Cayce Homes, all MDHA properties close to downtown.

“That’s what happens when you don’t make an investment in a community,“ says Larry Turnley, who grew up in the J.C. Napier homes in the 1980s and 1990s. “People see that you don’t care. That evolves into violence. When I was a kid, you might pick up a stick or a brick to ward someone off. Now, since you have guns so accessible, it’s going to be gun violence.”

As a young adult, Turnley was shot by police while fleeing from a porch late at night. The bullet is lodged in his upper thigh. After 20 years in prison, he returned to Nashville. He works with violence-interruption group Gideon’s Army trying to help young Black men avoid the mistakes he made as a teenager.

In 1991, Turnley shot down an MNPD helicopter with a handgun. In court proceedings, he explained an intense desire for acceptance and social pressure. Young Buck, an early member of G-Unit and perhaps Nashville’s most commercially successful rapper ever, cemented LT as a local legend by rapping about the moment in 2011’s “I’m Done Wit Y’all.”

“They respect me because I have credibility from my past,” Turnley tells the Scene under a pavilion in Hadley Park. “That opens up their ears. And I can go in and hit them with a positive message. Those stories have influence in our communities, so I can be out here as a violence interrupter, trying to stop gun violence or retaliatory gun violence.”

Raymond Kinzounza has a mini plastic water bottle next to the door to his office. It’s about half full with shell casings Kinzounza finds on the street and sidewalk outside the library, a growing collection that he started five months ago. He fled civil war in the Congo in the late 1990s. Kinzounza manages the Nashville Public Library’s Pruitt Branch, a two-story community space on Charles E. Davis Boulevard, the center of the Napier-Sudekum neighborhood.

“The identity of a library is defined by the need of the community,” Kinzounza tells the Scene. “What I see here, it breaks my heart. People come to us with spoken needs and unspoken needs. This library is a safe place.”

When the bottle fills up, Kinzounza plans to get a bigger one. He prevents maintenance from fixing the tiny holes high on the walls and the spidering cracks in the window, the marks left by bullets that strike the building.

“I want them to see how dangerous it is to be in this neighborhood,” he says. “These tell a story.”

Kinzounza participates in monthly community meetings with residents, police officers and local leaders. When drive-by gunfire picked up, he pushed for speed cushions on Charles Davis, a fix that, he says, slowed cars and reduced shooting. Now he’s asking Metro to ban Roblox, a wildly popular game among elementary and middle school students in his library’s computer lab that involves shooting and evading law enforcement.

Guns are not allowed in his library. Kinzounza has never considered owning one himself.

“Violence will always push people to more violence,” he says. “That is useless.”